- Home

- J. C. Davis

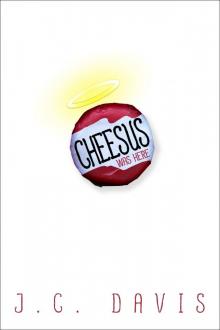

Cheesus Was Here

Cheesus Was Here Read online

Copyright © 2017 by J. C. Davis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are from the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Sammy Yuen

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1929-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1930-9

Printed in the United States of America

For my mom, who filled my life with books and taught me that a trip to the bookstore is always the best adventure.

CHAPTER ONE

Miracle on Aisle 4

Every Sunday my town turns into a war zone. On one side, St. Andrew’s United Methodist stands poised, huge church-tower bell at the ready. On the other, Holy Cross Baptist prepares to return fire as the choir warms up and the sound system is adjusted. I don’t want anything to do with either of them. Me and God, we’re not best buds these days.

I shove away from the convenience store’s counter, sliding my hands over the nicked orange surface, and count out my cash drawer. This is my first Sunday shift, and after the register is ready I raise a soda cup filled with Dr. Pepper as a toast. It took three weeks of begging and pleading before Ken, the owner, agreed to let me have this shift each week. Completely worth it.

No more hiding in my room and making excuses on Sunday. No more glares from porch-sitting little old ladies. No more lectures about my ungodly ways from PTA moms. They can’t fault me for drawing a paycheck. Probably.

Outside, St. Andrew’s bell rings, brassy and demanding. In answer, Holy Cross’s choir lead, Ellen Martin, belts out the opening bars of a gospel song through speakers wide as a barn door. Minutes later, the bell falls silent and Ellen draws out the last triumphant note of “Hallelujah.” I start laughing. Score one for Reverend Beaudean and Holy Cross. Pastor Bobby’s arms must have given out while yanking on the bell pull.

I slip on my neon yellow apron. The words Gas & Gut are scrawled across the top in Sharpie. The store is actually called the Gas & Gullet, which isn’t much better. The letters lle in the store sign were damaged during a storm ten years ago. Ken never bothered to replace them.

My name tag adds an extra layer of tacky to the shop clerk chic. It hangs at an angle, one corner curled forward like a dog’s ear. Ken wrote my name, Delaney Delgado, on the front using the same Sharpie as my apron and then slapped a piece of clear packing tape over top to keep the letters from smearing. This town is all class.

Clemency is tiny. Population 1,236. Nora Jean had her baby last week so I’m adding him to the tally. There are only two gas stations, the Gas & Gut and a new Exxon three blocks away. Jobs are scarcer than a business suit on Main Street.

It’s a long, slow day. The buzz-thwap of a fly beating itself against the front window and the wheezing cough of the ice cream chest provide a steady soundtrack. The AC stuttering to life in fitful bursts adds variety but isn’t enough to keep my T-shirt from clinging damply to my skin under the apron. I try to think icy thoughts.

Late in the afternoon, a black SUV pulls up to the gas pump out front and a man in checkered swim trunks and flip-flops gets out. His skin is a red so deep, tomatoes would be envious.

The back door of the SUV opens and two boys tumble out, also in swim trunks and flip-flops. Their sunburns are pale, washed-out reflections of the man’s. The first boy, perhaps twelve, leans over and punches his brother on the shoulder, eliciting a yell. The younger boy retaliates with a kick. Their father’s hand tightens on the gas pump handle and it looks like he’s about to yell. Instead, he reaches over and lightly swats their heads, one after the other, smiling.

While the three of them are distracted, I surreptitiously lift my camera and snap a picture. This is not as easy as it sounds. I don’t have the latest palm-size silver toy or a camera phone. My weapon of choice is a clunky Polaroid camera my grandfather gave me two years ago. It might have been new in the eighties when Pops got it, but now it’s so battered it looks like it was used as a soccer ball in the World Cup. It’s the most beautiful thing in the world.

When the picture pops out of the camera with a soft whirring noise, I yank it free. The boys and their dad are on the move; no time to fan the air and watch the image appear with its own brand of magic. I shove the camera and picture under the counter and straighten up, pasting on my best smile.

“Welcome to the Gas & Gut,” I chirp as they come inside. My voice is so chipper, I want to strangle myself with one of the licorice ropes.

The dad gives me a wary look but nods. Within five minutes, they’re gone, the boys clutching soda cups large enough to drown in. We should offer free flotation devices with those things.

I pull the photo back out and study it. Exhibit A: portrait of a family, fractured but not broken. Maybe their mom is just busy with her book club today. Or maybe she’s five states away shacked up with a boyfriend named Roy. Or maybe she’s buried and rotting in the ground. But she’s not here. And they’re still smiling. Proof that these things can happen. What’s the secret? I uncap my Sharpie and label the wide white band at the bottom of the picture with neat, precise letters: modern family.

I add it to my stack of pictures for the day, three deep so far. These are my proofs, my windows on the world. One day I’ll be able to line them all up and the world will make sense again.

Just before six, the end of my ten-hour shift, I make a quick check of the aisles and the cold cases.

“Crap.”

I forgot to restock the cold case by the register. Andy, the night shift clerk on Sundays, is going to complain about that for a week.

I snag the neon green basket that holds the Babybel cheese wheels. A single cheese remains, red cellophane wrapper bright as a new poker chip. My little sister, Claire, loved the stupid Babybels Mom used to tuck into our lunch boxes. My chest squeezes tight and I pick the cheese wheel up gingerly between two fingers.

“Hey, no bruising the merchandise!” Andy breezes in, his Gas & Gut hat clinging to the back of his head off kilter, shirt untucked, and a cigarette butt still hanging from the corner of his mouth.

I grimace. “Ken will rip you a new one if he sees you smoking in the store.”

Andy graduated from Shrenk High last year, but unlike anyone with half a brain cell, he’s chosen to stay in Clemency. When I graduate I’ll be out of this town so fast I’ll leave a sonic boom in my wake.

Andy plucks the cigarette butt out of his mouth and waves it at me. “It’s not lit. Ken can’t yell at me for a cigarette I’ve already smoked. Outside. On my own time. Now you,” he adds, “won’t be so lucky when Ken figures out you’re palming the merchandise.” He taps a finger against the we prosecute shoplifters sign propped against the cash register.

I flip him off. “I’m paying for it. Don’t get your panties in a wad.”

Andy grins back. “Sure, Del.”

Andy is cute in a middle-America kind of way, with farm-boy blond hair that sticks up in all directions and freckles sprinkled like a dash of cocoa powder across his skin. He’s a shameless flirt, but I can’t help liking him. Andy works a lot of the night shifts and every now and then we share a shift, though it’s rare. The Gas & Gut isn’t busy enough to need two clerks.

He catches sight of the empty bins behind me and groans. “Couldn’t you at least restock?”

“Yeah, sorry about that. I only just noticed they were out.”

Andy sighs, shoving his bangs out of his eyes. “Fine, I’ll restock. Beat it, would you? Cindy’s coming by later and I don’t need extra company.”

“You’re using the Gas & Gut as a hookup spot? Classy.”

“Jealous?” Andy croons. He walks behind the counter and pops the register open, doing a quick count and jotting down the cash total on a grotty old notepad.

“You wish.” I weave through the aisles, debating the merits of SpaghettiOs over Beefaroni. I finally grab the Os, a couple stale doughnuts, and a case of Dr. Pepper. Gourmet food all around.

I drop my purchases on the counter in front of Andy and dig in my back pocket for a twenty. Andy swipes the items across the scanner, pausing when he gets to the Babybel.

He glances again at the empty cheese basket.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” he says with mock dismay. “You’re not old enough to purchase this without a parent present.”

“Hand over the cheese or die.” I cock my finger like a gun and scowl at him.

Andy laughs but moves the Babybel to the other side of the counter. “You left me with stocking and you’re trying to run out with the last cheese wheel? I need my snacks, Del. This little cheese is payback for giving me extra work. Take your SpaghettiOs and walk.”

“That’s petty.” I drop the crumpled twenty on the counter.

As I grab my change and the thin plastic sack, Andy waves the Babybel cheese tauntingly at me. He’s such an idiot. The door sticks when I push it and I curse under my breath, shoving harder. It screeches open. Stupid, cheap-ass Ken never will fix the thing.

“Holy shit,” Andy says.

I glance over my shoulder only to find Andy staring down, slack-jawed, at the unwrapped cheese wheel in his hands.

He jerks his head up. “Get back in here! You’ve got to see this.” He puts the cheese wheel down as if it’s a live grenade.

What the hell? I abandon my shoving match with the door and head back to the counter. Andy points at the cheese wheel.

There’s something weird about the surface of the cheese. I lean closer and then snort, straightening. “Cute. My baby sister used to carve hearts into her cheese wheels too. Except she was five and didn’t flip out about it afterward.”

Andy looks at me like I’m speaking Swahili. “That’s not a heart some kid made and I didn’t Ginsu the cheese. It looked like that when I unwrapped it.”

I tilt my head, raising an eyebrow, and he twists the cheese wheel to face me. I laugh. “Seriously?”

Andy’s face flushes red. “It looks like baby Jesus. You see it too, right?”

“It looks a bit like a baby. He’s a little lopsided, though.” I move, trying a different angle. The folds and indentations of the cheese form a kind of picture, an infant wrapped in swaddling cloths like a tiny nativity piece.

Andy whips out his phone, snapping a picture. “No one’s gonna believe this. Holy cheese! Maybe it’s like a sign from God or something.”

“You think God is talking to you through dairy products?”

“All I know is that is beyond nuts.” Andy pauses, fingers poised over his phone while he posts the picture. “Hey, didn’t some holy tortilla sell for a couple thousand online a few years ago?”

“No one’s going to buy that.”

“Don’t be so sure. This thing could be worth a lot.” He pockets his phone and edges the cheese away from me.

“Good luck,” I say with a laugh. Sometimes Andy is weird.

I drop my backpack off my shoulder and unzip it, hunting for my camera. I don’t have a picture of holy cheese, might be nice to add it to the rest of my collection. Proof that weird stuff happens?

“Mind if I snap a pic?” I hold the camera up for Andy to see.

He covers the cheese wheel with a cupped hand, blocking it from view. “I already sent a picture to my blog. No way you’re scooping me on this and posting it to your Facebook.”

“It’s a Polaroid, genius. Real pictures? Remember those? I’m not going to post pictures of your precious cheese all over the Internet. I want one for my wall.”

Andy looks dubious but less likely to bolt. “Just one?”

“Yeah, just one.”

“Fine, but you better keep it to yourself.” He moves his hand, but stays close enough to snatch the cheese wheel away if I make a move for it.

“You’re paranoid. You get that, right?”

“The rest of the world’s gone digital, you know.”

I hold the camera poised over the cheese wheel and bend to line up the shot in the viewfinder. Moments later, the picture slides free and I watch the image fade into life. “I prefer this, it’s more honest. No photo manipulation, filters, or digital crap.”

Andy shakes his head, picking the cheese wheel up again and tucking the cellophane around it.

This time, I don’t look back when I walk out of the door.

Everybody always thinks they’ll know the exact moment their life skips onto another track, the moment the meteor shifts in its path and hurtles toward Earth. I didn’t see this meteor coming. Didn’t even realize I’d just snapped a picture of it.

CHAPTER TWO

A Family of Ghosts

We live on the other side of town from the Gas & Gut. A few cars pass by as I walk and I wave at the drivers I recognize. They wave back. The sidewalk is cracked and pitted, concrete squares squashed together as though a drunk arranged them. The edges don’t line up and if you’re not careful, it’s easy to trip and do a face-plant. I’ve walked this way so many times I automatically match my pace to the uneven squares. My own little game of hopscotch right up to our front yard.

In the distance, squat hills and scrubby trees form a backdrop for the town’s low buildings—nothing over two stories. Downtown is a child’s building block set of mismatched rectangles in competing colors: the bright pink door of Beatrice’s beauty parlor in stark contrast to the subdued white concrete of Community Bank sitting next door. In the middle of the town square is a park no bigger than a baseball diamond. A gazebo with peeling white paint perches at its center, and a neglected set of swings and a rusting slide take up the far corner. In summer the entire town swarms that tiny lot for the Watermelon Festival and again in fall for the annual fish fry. Veterans Day will fill the park with old people in uniforms. The town square is the heart of Clemency. Except on Sundays.

Our house is decent by Clemency standards, two stories when most houses in town are one. The yard used to be nice, with wild rosebushes and neatly trimmed hedges lining the front of the house. Now the hedges have turned rogue and attempt to scale the brick walls. The grass was swallowed by weeds two years ago and forms an ankle-deep patchwork of greens and muddy brown. Crossing the tiny front porch, I stomp on drifts of dead leaves. Claire and I used to have leaf fights every fall, flinging fistfuls at each other’s faces until our hair was tangled and filled with leafy confetti. I stomp on the leaves harder.

Crickets begin to chirrup and a car drives past, its tires making a soft shushing noise against the asphalt. Next door, Mrs. Abernathy’s TV is on, and the murmur of voices slips out her open kitchen window and wraps around me.

Inside my house, there’s only silence waiting, just like every other night.

I could circle the block a few more times, but the grocery sack is so thin I’m afraid the cans will come tumbling through the bottom any minute.

The front door is barely open when my older brother, Emmet, barg

es into the hallway. I drop the grocery sack with a shriek. “What the hell?”

Emmet grins, looking way too pleased at having scared the crap out of me.

“Jesus appeared at the Gas & Gut and you didn’t call?” he demands.

“Jesus didn’t make any doughnut runs while I was on shift,” I mutter, dropping my keys into a little blue bowl on the entry table. I ignore the stack of mail sliding off the table edge. I already fished out this month’s bills and shoved them under Mom’s bedroom door two days ago.

Emmet hasn’t changed out of his football uniform and there’s a trickle of sweat running down the side of his face. He must have been doing extra drills after the rest of the team packed it in and then run all the way home in his heavy gear. My brother the superjock. High school football is his god. Luckily for him, the rest of the town also loves to worship at the altar of Astroturf. Friday nights are pretty much a high holy day around here and the only time Holy Cross and St. Andrew’s declare a temporary cease-fire.

“Heidi texted me five minutes ago. Said she saw something on Andy’s blog about Jesus appearing,” Emmet says. “I knew that guy was a stoner.”

“Since when does Heidi read Andy’s blog?” Guess I’m even more out of the social loop than I thought. Also, who still blogs?

Emmet shrugs. “Heidi said Mary called and told her to check it out.”

“It’s been like twenty minutes. Unbelievable.” I don’t know why I’m surprised. It’s not like there’s anything to do in this town except talk about everybody else’s business. But even by Clemency’s standards, that was fast.

“Are you saying it really happened?”

I shove the grocery sack into Emmet’s hand. “Dinner. SpaghettiOs. Fix us both a bowl and I’ll tell you all about it.”

Emmet glances upstairs, weighing the sack in his hand.

I shake my head. “You know Mom will be out the door any minute.”

Emmet’s shoulders stiffen and he turns, shuffling into the kitchen with the plastic bag banging against his leg. A few years ago, Mom would never have missed a family dinner. Of course, a few years ago she would have been cooking.

Cheesus Was Here

Cheesus Was Here